The Legacy of Women in Design

Words by Viviane Stappmanns

Stories

29.06.2022In 1927, 24-year old architect Charlotte Perriand (1903-1999), approached Swiss architect and designer Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (1887-1965), better known under his pseudonym Le Corbusier, to apply for work at his studio in Paris. The visit was brief: he is said to have rebuked her with a gruff “We don’t embroider cushions here”. Just a month later, Le Corbusier found himself at Perriand’s 1927 Salon d’Automne exhibition Bar Sous le Toit, her seminal first foray into the realm of curved, tubular chrome that is so well-known today. He immediately hired her to run his furniture design business. As such history powerfully illustrates, in design, stereotypes can be pervasive—but they don’t need to prevail.

In the narrative of modernist design, women are repeatedly cast in domestic roles while a handful of celebrated and interconnected hero figures are the revered leads. Gropius, Breuer, Johnson, Le Corbusier, Beyer, Nelson or Loewy—they visited and worked at the same prestigious schools, and were connected through friendships, feuds and loose ties with other members of their exclusive all-boys clubs. This is not a revelation. But since the 1970s, singular and collective efforts by feminist scholars—mostly from art and architecture, rather than industrial design—have worked to redress the balance.

In recent decades, many prolific and influential women have been rediscovered, their working biographies painstakingly reconstructed, their archives preserved, and their stories told to large audiences via exhibitions and publications. Among them are the likes of Brazilian architect Lina Bo Bardi (1914-1992) and the Bauhaus Women, and the so-called “Damsels in Design”—a group of designers who worked at General Motors in the 1950s after management realised many car purchases were instigated by women.

Importantly, looking at women in design reveals more than simply lost and obscured names. Revisiting and

assessing the contributions and achievements of female

practitioners can also equip us with tools to construct a new

understanding of a more diverse, inclusive practice of design

for the future. A full assessment is beyond the possibilities

of such a short article, but here are three quick lessons with

which to begin.

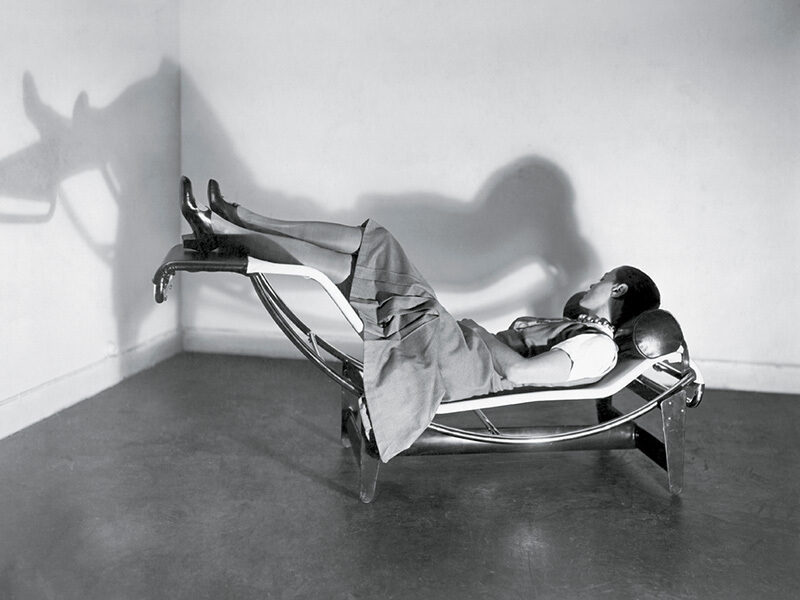

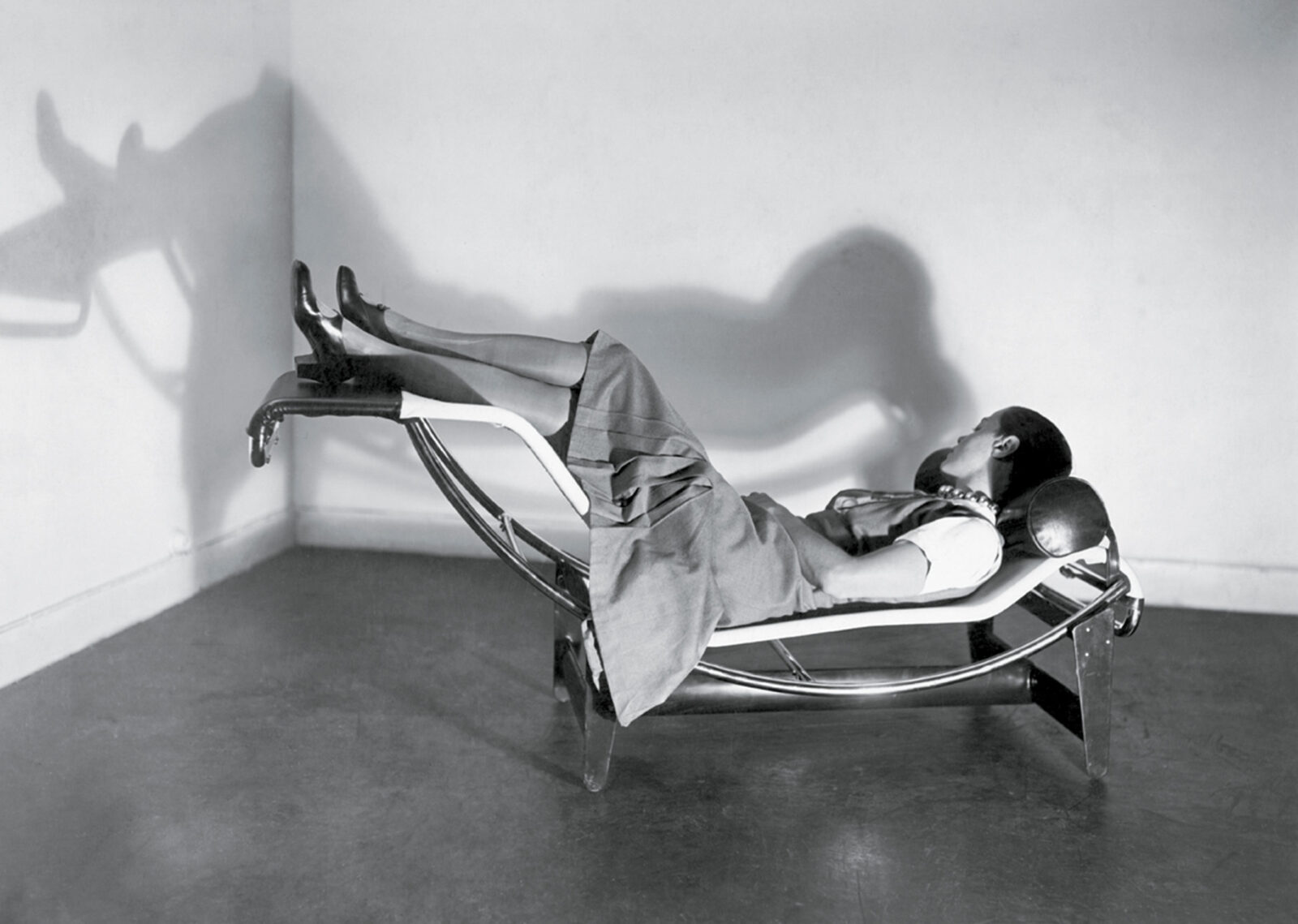

Salon d’Automne 1929, Charlotte Perriand on LC4 Chaise longue à reglage continu, Le Corbusier, Jeanneret, Perriand © Archives Charlotte Perriand.

"Far from being historical footnotes, women designers through the past century have created a legacy of smart, socially-minded design that continues, and is even more prescient, today."

Lesson One: Our systems of value are out of date

Throughout design history, just as today, a prestigious education and potent network has been a guarantee of success. For anyone who doubts the truth of this, I recommend perusing the participant lists of get-togethers

such as the International Congresses of Modern Architecture

(CIAM), founded by 28 architects in Switzerland in 1928, or

the International Design Conference in Aspen, inaugurated

in 1951 in the eponymous resort town in Colorado. Both

reveal that the agenda-setters of that time were intimately

connected, looked out for each other when it came to

arranging for work, teaching gigs at Harvard or publishing

one another. Such exclusive networks, to this day, serve to

provide a seal of approval: “They studied at xyz”, “They work

with xyz”.

But it is precisely this attitude that gives us blinkers. Take,

for instance, Eileen Gray (1878-1976). Although privileged

and wealthy, Irish-born Gray battled gender stereotypes

throughout her career. She opened her first gallery in Paris

under a male pseudonym, Jean Désert, in 1922, and later

became renowned for two iconic buildings and their interiors

she designed—one for her partner, another entirely for

herself—at France’s Côte d’Azur. Gray’s flexible, thoroughly

modern work stands out because her design and architecture

skills were not formally acquired—she had trained as a

lacquer artist. Yet the chrome, steel tube and glass furniture

she exhibited in 1925 was in every respect as modern as that

of her well-connected, formally trained colleagues Mies van

der Rohe and Marcel Breuer, who produced similar designs

that same year.

Gray spent her last decades living a relatively secluded life and only found recognition shortly before passing away, aged 98, in 1976. Today, Gray’s designs are among the most revered at auctions, and her work has been the subject of retrospectives at several prestigious institutions, but the system that first let her fade into obscurity still exists. As this article is being published, designers of any gender might be missing out on opportunities or recognition because they don’t know the right people, come from the wrong country, or went to the wrong school or none at all. It’s time to let go of systems of value that are based on institutional networks and connections alone.

Lesson Two: Design was always social

In today’s post-capitalist society, many designers—

especially those just embarking on their career path—are

looking to set up practices in service of the greater good.

For too long, design has been the bedfellow of greedy and

ecologically questionable businesses. But for the past decade

or so, the practice of and discourse around social design has

been taught and discussed at a number of universities. But

this is not a new kind of design. A long line of role models

can be found among female practitioners, many of whom

were never before discussed in a design context, yet who

provide a path forward toward a different design practice.

One of these protagonists is Jane Addams (1860–1935), who in 1889 joined forces with a college friend, Ellen Gates Starr (1859–1940), to establish one of the United States’ first settlement houses in one of the most poverty-stricken areas of Chicago.

Modelled on the British example, Hull House catered to the needs of a swiftly growing immigrant population by offering literature, history and art classes as well as crafts workshops and childcare. Addams’ approach might today be thought of as transformation design. Together with her allies, she painstakingly mapped the origins, social strata, profession and needs of the community members around Hull House, to then tailor the programme accordingly and introduce participatory approaches to the workshops conducted at the institution.

Further South in Boston, Louise Brigham (1875–1956) designed simple pieces of furniture built from standard wooden packing crates. A complete suite of her so-called “box furniture” cost no more than four dollars—half an average weekly wage in those days. Her how-to manual, Box Furniture, was published in 1909, long before Gerrit Rietveld in the 1930s and Enzo Mari in the 1970s brought design status to DIY. Brigham’s book went through several editions and was translated into many languages, but she, too, is almost forgotten today.

Even the aforementioned Charlotte Perriand, whose

works today are among the most valued by a female

designer, initially set out to create low-cost solutions for the

less privileged members of society. This is what had drawn

her to work with Le Corbusier, who at the time was working

on his master plans for redesigning or inventing entire cities.

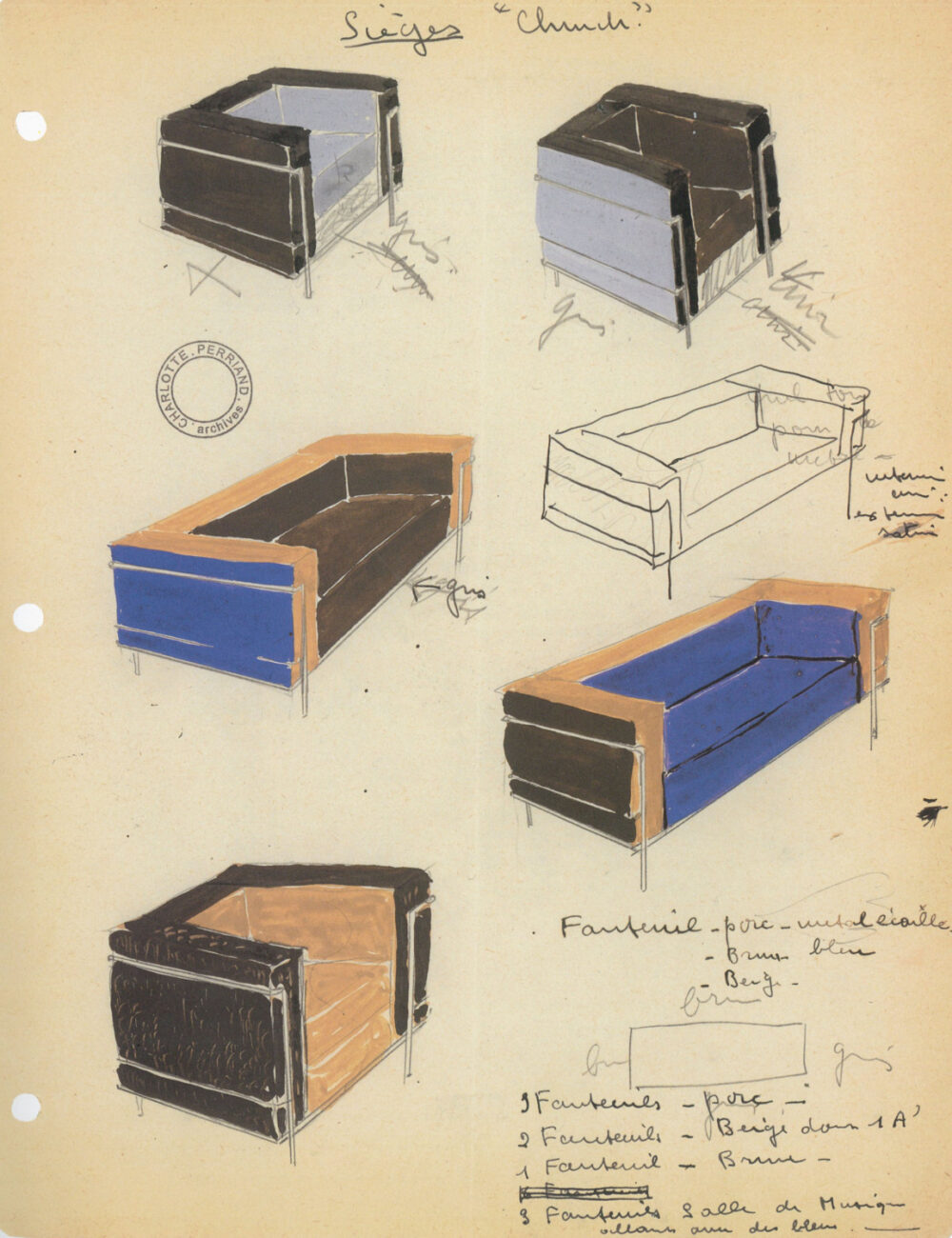

Research drawings of various polychrome versions of the Fauteuil grand confort (small and large models) for Villa Church, Charlotte Perriand 1928. © Archives Charlotte Perriand.

Some of Perriand’s most lauded designs today were initially designed for modest budgets, like her Antony bookcase, which she worked on with atelier Jean Prouvé to furnish student housing in Paris. Not only the formal work but also the processes and intentions of women like Addams, Brigham or Perriand—as well as other yet-to-be- rediscovered social reformers or designers, I imagine—should be considered as we seek to redefine the future practices of design.

Lesson Three: Consider collectivities and syntheses

Across design history, the biographies of many female designers illustrate a picture of design as a practice dedicated to issues of social and environmental justice. A recurring theme is a penchant to do things differently, to interrogate, and in some instances turn existing conventions entirely on their head.

The London architectural collective Matrix, for instance, was founded in 1981 to address the relationship between gender and the built environment. Combining both a practice of research and one of building, the group of women worked within a democratic, self-governed and hierarchy- free framework and produced its designs in community consultation processes. Both participatory design processes, as well as collective work structures, are being rediscovered today. Now that Covid has finally alerted companies that Fordist structures of hierarchy may be a thing of the past, we can look no further than Matrix when searching for inspiration to redesign work culture.

Life at the Bauhaus: Group portrait of the weavers behind their loom in the weaving workshop, Bauhaus Dessau, 1928. Supplied: Vitra Design Museum. © Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin.

Nuage bookshelf, designed by Charlotte Perriand (1952-56) - Cassina. A modular shelving system that can be rearranged in a variety of configurations.

Meanwhile, outfits like

the Turner Prize-winning collective Assemble are already

practising the multi-disciplinary, community-oriented approach that Matrix first pioneered. There is also a lesson in the way many women have had to shape their career paths. Here at Vitra Design Museum,

in the course of research for our exhibition Here We Are!

Women in Design 1900–Today, our team spent a year pouring

over the biographies of more than 150 women designers

across history. It was surprising to find how many of them

had to pivot or, in some cases, entirely pause their careers

for long periods. Naturally, many of these interruptions were

due to changes in family circumstances, such as in the case

of Hungarian-born Eva Zeisel (1906-2011), whose 70-year

career as a ceramicist also included being one of the first

women to receive a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern

Art in New York (in 1946). She stopped working in design for

years to work with her husband on sociology projects—only

to then continue her prolific career, actively working until she

passed away at 104.

In a recent conversation, Patricia Urquiola (b. 1961), one of the most celebrated furniture designers today, reminded me that we should see these changes in a positive light. Herself a highly versatile designer who oscillates between designing objects and spaces and creative direction, Urquiola pointed out that women’s trajectories show us we needn’t be bound to one career path. “I want to reserve the right to do something very different if I wish to,” she told me. She suggests that for centuries, women’s lived experience consisted of juggling many different tasks and wearing many hats—and that flexibility, for her, far from a hindrance, is the key to a successful career. It may just be the reason we see many more women succeed in future design practice, which will require more interdisciplinary, cross-boundary thinking.

Examples of this can be found in the practices of contemporary designers Nipa Doshi (b. 1971) and Gunjan Gupta (b. 1974), both Indian-born women who combine pluralistic cultural references in their work and run highly successful studios—Doshi in London, Gupta in Ahmedabad. Others like Christien Meindertsma (b. 1980) have developed unique approaches to design, forging synergies with other disciplines. Meindertsma thoroughly interrogates materials and processes, fusing investigative research, science and design. German-born, Finland-based designer Julia Lohmann (b. 1977) has created a global network of designers and associated thinkers and artists, all of whom share a passion for investigating and sharing their insights on algae and seaweed. In today’s hyper complex material and manufacturing environment, this kind of design, based on knowledge sharing and community action, appears to be the only way forward.

Charlotte Perriand and Pierre Jeanneret's Refuge Tonneau at Cassina's historic headquarters. Designed in 1938, the Refuge was intended as a space for reflection. Cassina replicated the original design in 2012 based on numerous drawings; it is the only authentic reproduction in existence.

"In recent decades, many prolific and influential women have been rediscovered, their working biographies painstakingly reconstructed, their archives preserved, and their stories told..."

Tokyo Chaise Longue designed by Charlotte Perriand (1940) - Cassina. Demonstrating exceptional wood working mastery, the Tokyo Chaise Longue is an organic and inviting armchair. Available in teak and bamboo, the recliner is composed of 12 curved strips of wood.

Charlotte Perriand in the country, 1934. Photography by Pierre Jeanneret. © Archives Charlotte Perriand.